Matthias Muhar received the Marie Curie (MSCA) individual fellowship

Congratulations to our Postdoc Research Fellow, Matthias Muhar, who received the Marie Sklodowska-Curie Actions (MSCA) individiual fellowship which belongs to the EU Horizon 2020 program.

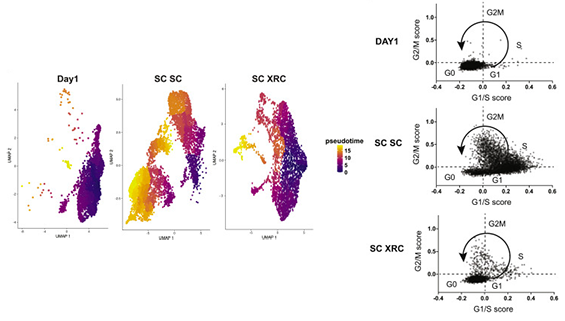

Jenny then had a very creative idea. She asked if a previously reported

Jenny then had a very creative idea. She asked if a previously reported