Genome-wide sgRNA libraries for knockout screening are all the rage, and researchers have very generously made them available on Addgene. But which one...

READ MORE

Genome-wide sgRNA libraries for knockout screening are all the rage, and researchers have very generously made them available on Addgene. But which one should you choose for your project? Data is always better than guesswork, and I’ve started looking at what’s out there in a relatively systematic way. Note that this is a work in progress, so results will probably change a bit, but the general gist will probably be similar. Also, details in scoring of guides is a controversial topic, so for now let’s discuss stick to big picture themes everyone can probably agree upon.

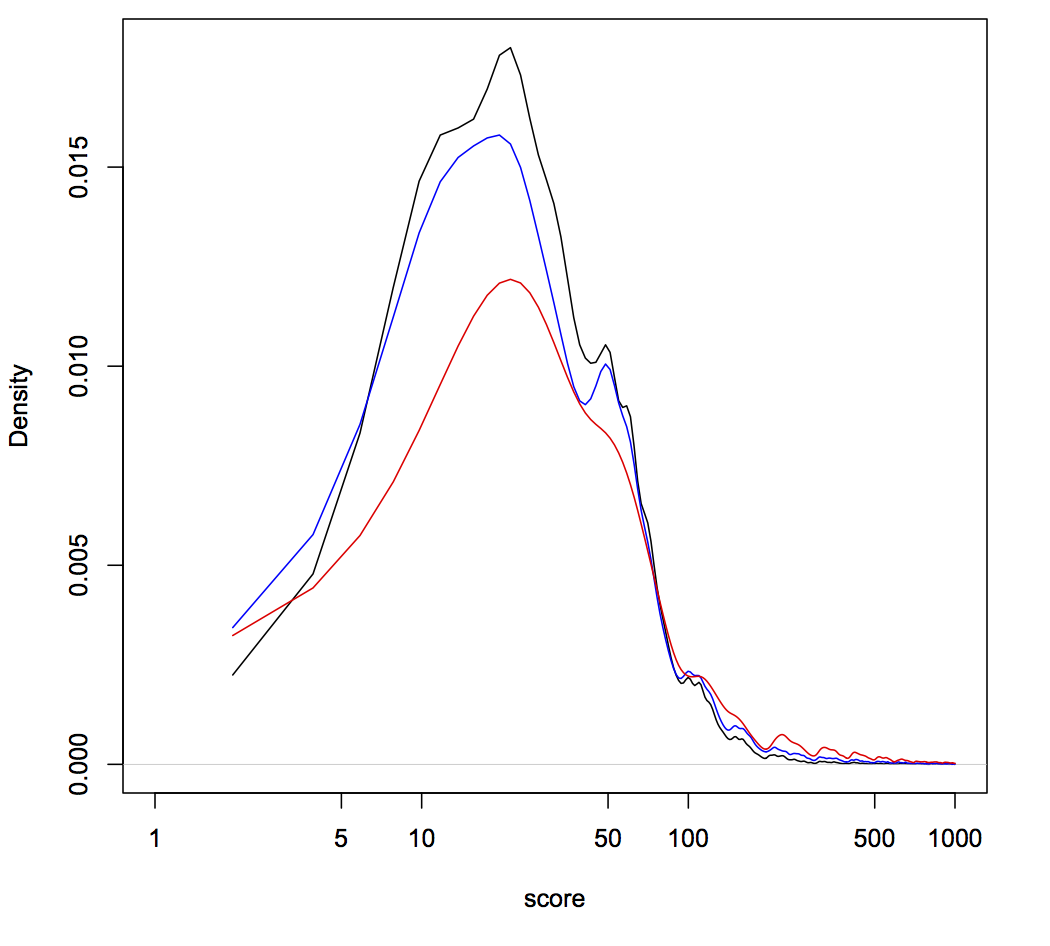

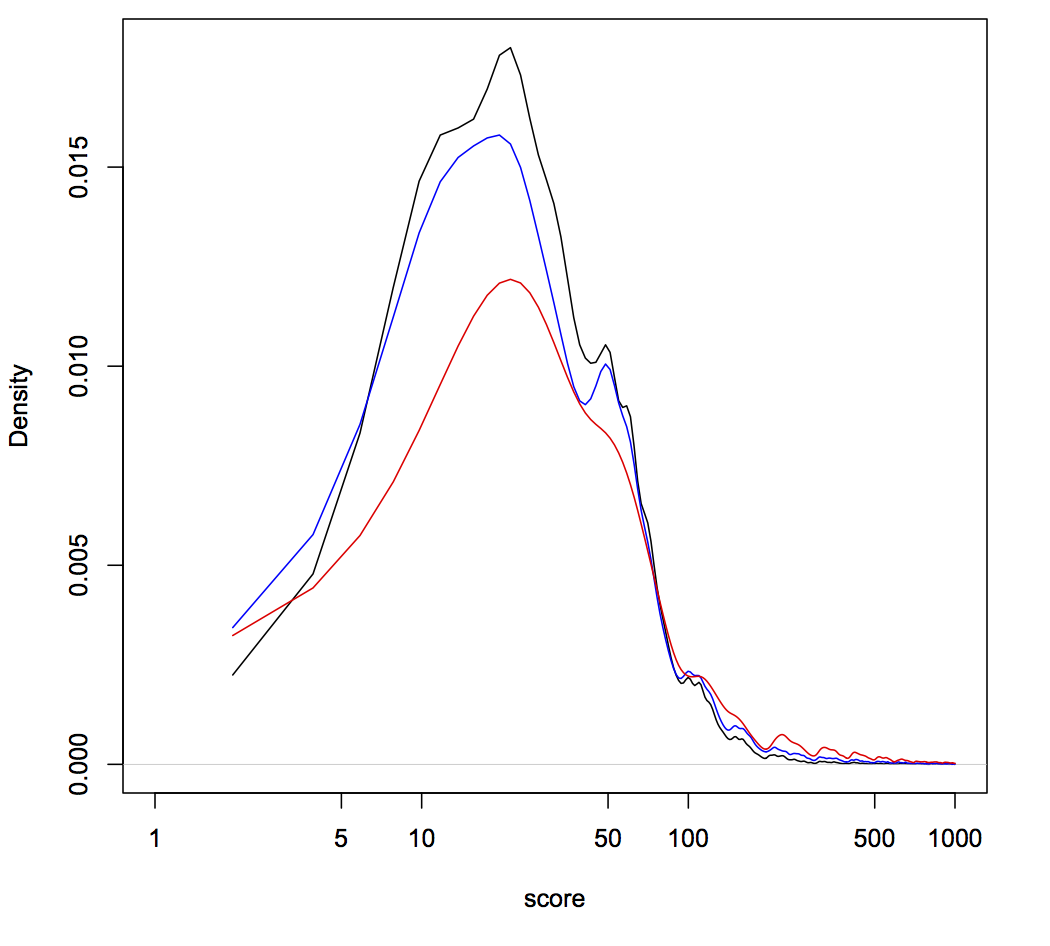

Below is a smoothed distribution of scores (lower is better, scale is arbitrary), based on several metrics for three different guide libraries related to two papers (score on the x-axis and frequency of that score on the y-axis). Why three libraries for two papers? Turns out one Addgene-deposited library isn’t the same as what’s tested in the paper. Thankfully the authors were very transparent and deposited both sets of sequences into Addgene. Kudos to them!

The first thing to notice is that most guides score below 50. That’s good! It means those guides have only been penalized for relatively trivial things. Hence, the libraries are pretty good and most guides should be functional (a no-brainer, given the awesome papers on these libraries). The second thing to notice is that some libraries have a peak around a score of 50. That’s bad, because 50 is the penalty added to guides containing Pol III terminator sequences. These are likely to be useless guides, since they won’t even be fully transcribed, but at least they should be silent in the library. The third thing to notice are the jagged peaks above a score of ~100. These guides are relatively rare in the libraries, but are potentially scary. Guides can only get a score this high if they have likely off-target sequences that occur within coding regions. In fact, guides get +100 for each off-target coding region. So the saw-tooth pattern >200 represents guides in these libraries that could potentially knockout more than one gene other than the one target. Hence, when using these libraries it’s very important that your phenotype of interest occur with more than one guide (as stressed in the papers). Trusting just one guide could lead you very far astray due to off-target effects.

The above isn’t mean to dissuade anyone from using these libraries. They’re an incredible and unprecedented resource and the originators have done the community a huge service by making them available for a nominal fee on Addgene. But I think all seasoned scientists know that it’s dangerous to treat things as a black box, and that looking under the hood never hurts. I’m sure library improvements will be a hot topic for some time to come and that can only be a good thing for people who want to use these for new biology.

X Close

Welcome to Lena Kobel, who joins the lab as a Cell Line Engineer. Lena has a long history in genome engineering, with previous experience in Martin Jinek’s...

Welcome to Lena Kobel, who joins the lab as a Cell Line Engineer. Lena has a long history in genome engineering, with previous experience in Martin Jinek’s...